A couple of weeks ago, I ran an experiment on my website. I made it conversational. The feedback, responses and media coverage have been absolutely amazing. I received over 300 emails within the first 24 hours.

Thanks to everyone who was kind enough to talk to my website. It was a great chat. 🙌

Some of you asked me to share my insights. Since this whole thing started as a conversation, I’d like to keep it as one.

So here we go. 💬

M y mom always told me that nothing good comes out of fear and yet, fear is an incredibly powerful tool. It forces us to change and grow in order to overcome it.

The idea of making my website conversational came from a simple question I shared on Twitter and LinkedIn a couple of weeks ago.

What will you do once bots take over and designers are no longer needed?

That was a bit of a joke question, but I didn’t expect this simple and straightforward reply:

“Fire you!” — Raphael Leiteriz, Director Product Management at Google

Raphael is an incredibly nice person. He was obviously (hopefully) joking and yet, his words made me think:

How will designers like me fit into the conversational era?

Perhaps more importantly, what impact will this have on the craft of UX design as a whole? Is this whole movement for big companies only or can anyone be part of it? Was the notifications hype we saw during the last two years really about conversational interfaces all along? Question after question…

I decided to overcome my fear and get some hands-on experience. I turned my website into a chat. You can see it in action here.

Spoiler alert: If you occasionally talk to yourself in front of the mirror, you will have a blast building your own chat bot.

All right, let’s start. Here are 9 insights I gained along the way…

1. Writing becomes more and more important to our craft

As I started this experiment, I thought I would probably spend the lion’s share of time designing and programming. I was wrong.

Writing took significantly more time than both design and programming combined.

A crucial part of creating conversational experiences is the conversation itself. In other words… words. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that writing is the most time consuming part and yet it did.

I started drafting the conversation in iA Writer.

I then developed a concept of “conversation paths”: A small portion of chat messages that can trigger another set of messages. Conversation paths allowed me to design and model most conversations I wanted.

It was a good start. But it wasn’t enough.

2. Isolated messages don’t feel human

When talking to a person in real life, the conversation’s outcome — to a high degree — depends on how it started and how it evolved. In most cases, it’s awkward to repeat a topic. Once you talked about the weather, you want to move on to more interesting topics and probably avoid the whole weather discussion altogether.

In order to avoid repetition and robotic messages, I had to change the way I approached testing.

Instead of simply ensuring that all the conversation paths would work from a functional perspective, I clicked through each one of them to make sure they also work from a social perspective.

I was surprised how much of a difference this made. I discovered lots of scenarios where the conversation didn’t feel natural just because there were subtle repetitions or slightly odd connecting sentences.

We can’t think of conversations as isolated messages that we can stack on top of each other. We need to take into account the whole course of a conversation to make it feel natural.

3. Delightful details

Delightful details are about flirting with users.

Details in writing and the use of technology can make a critical difference between a conversation that feels lame and a conversation that sparks your interest.

For example, refreshing the page changes what the bot says. Instead of just saying “Hi”, it will now say: “Welcome back! 🙌”. It will even subtly change the conversation path— something I’ll cover in more detail in the conversational context learning.

So what happened here?

When people noticed this for the first time, they understood that the bot was smarter than they thought it was. It changed the way they thought about the interface. They suddenly started wondering:

What else can this thing do?

When creating experimental interfaces, one thing is for sure: People will fool around with it. One of my goals was to seamlessly integrate the classic contact form as part of the conversation.

Tapping on “Get in touch!” let’s the user type a custom message:

And that’s where things got messy. Not only did many people want to talk dirty to my bot, many would also provide a wrong email address. I designed my bot to be helpful, not naughty. So I had to come up with something…

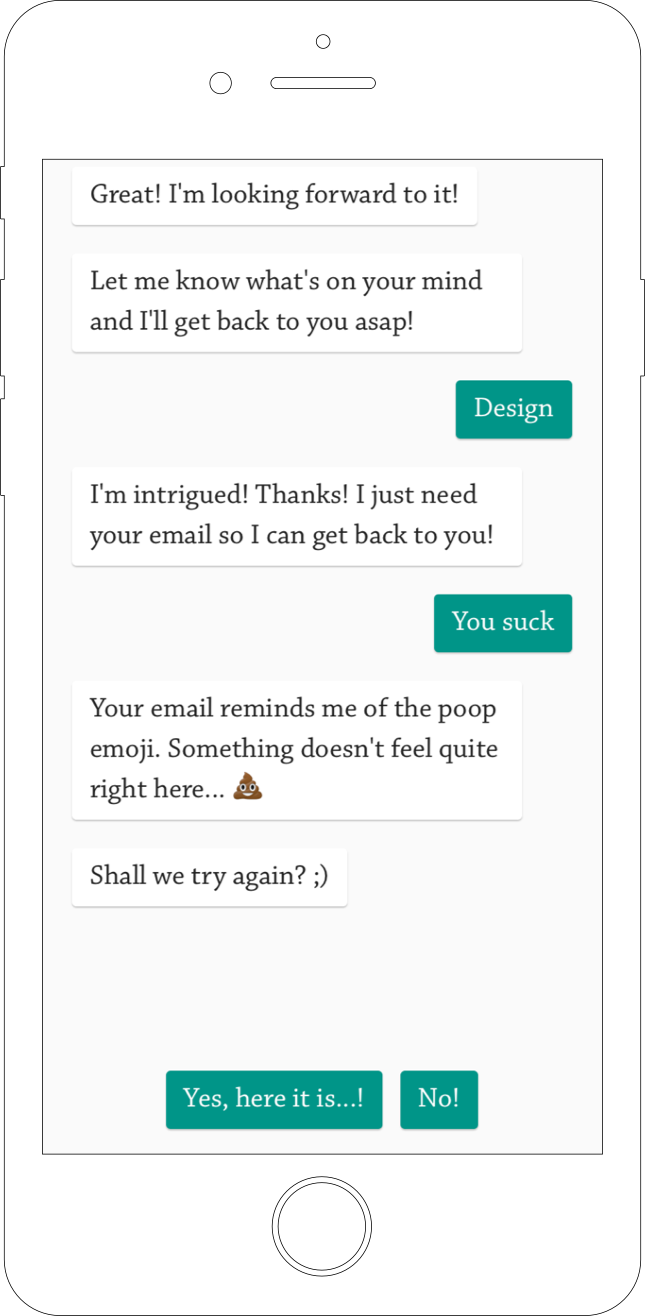

I started adding email validation: “Your email reminds me of the poop emoji. Something doesn’t feel quite right here…”

The conversational validation made people smile and tweet about it. They felt caught and probably thought “Damn, I thought I would get away with some gibberish”.

The lesson?

When people start messing around with your interface, you start messing around with people. It’s natural, delightful and part of dating the user.

I won’t spoil the rest. Maybe you’ll find some other hidden gems. 🤗

4. Conversational context shapes topics

Imagine you’re a designer going to a fancy cocktail party. You know most people there are designers too. Would this affect the way you start a conversation?

For most people, it would.

Instead of opening a conversation with “Hey, how’s it going, are you enjoying the freshly made banana shakes?” you might say something like “Hey, are you a designer too or what do you do?”.

The second conversation starter is contextual to the overall theme of the evening, whereas the banana one is more entertaining and less serious— especially at a fancy cocktail party.

For most people, it‘s easier to start a conversation with a more rational question, even though the emotional one would probably leave a longer lasting impression. I’m sure you had similar experiences at one of those “networking” events where the weather was the number one trending topic.

So I wondered, how can I integrate the concept of a contextual conversation starter to the experience?

Understanding context can greatly improve the way we initiate a conversation. When a person visits my website from Medium or Twitter, chances are much higher that they’re interested in design. They might have come across a tweet, article or other reference on one of those platforms. I wanted to add this thought to the conversation :

People who accessed my site from Kenny Chen’s UX newsletter were also surprised as the bot started the conversation by saying: “Looks like you’re visiting from Kenny’s awesome newsletter. You’re probably in design too, right?”

This small adjustment didn’t just improve the conversation’s flow and make it more human, it also made some of its features more discoverable.

More about this in the next section.

5. The hidden “specials”

My website can suggest UX articles in a Quartz-style interface. But unless I know for certain that users are interested in UX, I will certainly not start bothering them with it.

It would feel utterly strange. Like chatting up a complete stranger on the street and starting a debate about why we should ditch the hamburger menu in mobile design.

Knowing that the user came from Medium, allowed me to seamlessly transition the conversation’s topic by asking the user a contextual question:

Are you perhaps in the UX field too?

Answering “yes”, makes the chat bot talk about recent UX articles including personal thoughts of mine. It will however never recommend the same article twice since we want to avoid repetition, right?

A more challenging aspect of this is to get out of the article discussions again. But that’s for another time. 🚶

6. Timing changes interpretation

In my talk about meaningful motion in design, I discuss how duration can change the way we feel about our actions, our environment and even our perception.

But time transcends animation or any other topic. Time is ubiquitous. Not surprisingly, it’s also highly relevant in the field of social dynamics.

Imagine you just met a person you really like. You exchange numbers and can’t wait to meet that person again. When should you text that person? Should you text her immediately, or should you wait? But for how long?

Time can work both in and against our favor. It’s so subtle and elusive that it’s hard to understand how it can impact and even change the meaning of our words.

Let’s imagine you just texted Anna:

Hey Anna, it was really nice to meet you! — Bob

Now… Which type of response do you appreciate more, an immediate response or a response within the next three days?

No matter what your preference, one thing is for sure: response time will affect your interpretation. While the instantaneous response will yield immediate positive feelings, the delayed response will include a magical additional ingredient: anticipation.

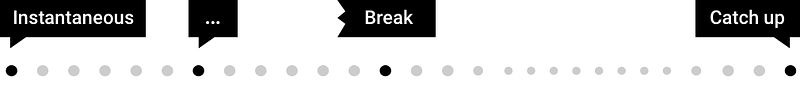

Without going in to too much detail, anticipation and delay greatly impact our appreciation and the way we communicate. I believe there are four different stages of time gaps that are relevant for conversational experiences:

Instantaneous < 10 Seconds

You get the response straight away. It’s the default in an ongoing conversation that’s happening right now.

Thinking > 30 Seconds

When a person takes a little longer to respond. For example, you’re chatting with your boss and she texts you: “Why are you late today?”. You will take a couple of seconds to come up with a creative explanation before you start typing a response.

If a conversational experiences indicates typing activity, lots of additional dynamics that exist in a real world conversations gets added. This dynamic is often lost in digital communication.

Longer Break > 1 hour

This gap usually means that the person was interrupted and he or she will get back to you later. It communicates busyness and is a crucial tool in todays communication both in business and private life.

Catching up > 3 days

When the conversation got lost and you either get back to the person apologizing for the delay, or by kicking off an entirely new topic.

Due to the simplicity of my experiment, I only played with the first category. I added a typing animation which has a variable delay based on…

– The length of the message

– The amount of space it will take up on the screen

These two variables ensure two things. First, the experience feels more human because a longer message takes longer to type.

Second, it ensures that the conversational partner can digest each message. When a chat bot sends a video, it can take a significant amount of space on the screen, if a video and long text are sent in short succession, it immediately feels like you’re talking to a bot. It feels spammy.

A more sophisticated chat interface with natural language processing could even add other psychological elements like hesitance to the first category.

“Hey Siri, should we go out tonight?”

…

stops typing

…

“I’m not sure… should we? 🤔”

Time incorporates many of the most important elements of rhetoric and it’s an inalienable asset of conversational experiences.

7. Animation becomes part of the conversation

Motion has a huge impact in how we feel about an interface. It can do, what traditional information architecture can’t: establish relationships in an observable, interactive way.

I spent quite some time refining the motion curves and the way animation works. In fact, I believe animation was an important reason why the reception was so positive in the first place. I would even go as far and say:

Without animation, there’s no conversation.

Let’s see why.

FIRST, animation adds a dynamic to the interface. A dynamic that becomes part of the natural characteristic of a conversation itself.

The subtle bounce back animation reinforces the playfulness of how I’d imagine chat bubbles to appear in a comic (depending on the type of comic, the animation would differ but here, it’s a serious comic).

SECOND, animation grabs attention. Once the chat bot finishes talking, two options animate in from the bottom. I kept refining the delay between the last message and the first button that appears at the bottom. At some point I found the delay that made users focus on the buttons right after the bot finished typing…

THIRD, animation reinforces the idea of interactivity. Animating the buttons in a slightly playful way grabs attention and invites the user to play with it. And indeed, tapping on a button let’s the button become the message itself.

This animation is in fact one of the most crucial of all.

Why?

Because it changes the way people feel about the conversation. Lots of people asked me which natural language processing technology I used. At first, I didn’t understand why anyone would ask me this but then it dawned on me:

The fact that people can observe how their choice becomes part of the conversation changes how they feel about it. Users suddenly felt like those were their own words, their own choices. Whereas without animation, there was a disconnect. Without animation, the conversation felt scripted and unnatural.

Animation didn’t just enhance the experience of my experiment, it was an essential part of it.

8. A chat can convey things a website can’t

With clever punch lines and carefully crafted headlines, advertising and web agencies try to differentiate themselves from one another. I do the same. I call myself a coffee enthusiast. How creative, huh? 🤗

But trying to be different can sometimes have the opposite effect. We either go too far and become too different, or we try so hard to be different from everybody else that we end up not being different at all.

My conversational experience lives on top of my website. Scrolling down reveals my traditional website. The first time I skipped the conversation I was shocked.

There was a significant disconnect between the two experiences.

My website’s design is what some would call very Swiss. It has a lot of whitespace, it’s pretty minimalistic and there are almost no colors in it. In short, it’s not exactly emotional. 💩

The chat bot on the other hand sends emojis, laughs and makes jokes. It has emotions. In other words: it has personality.

Those two design approaches both convey a different subset of my personality. The more rational side reflected by the traditional website; and the more emotional one, the conversation.

Design is always a reflection of ourselves. The conversational experience adds a more vivid and complete reflection of who I am.

9. A conversation can leave the canvas

When we think about conversational interfaces, we often think about chat bubbles on a rectangular screen. What if a conversational experience all of the sudden leaves the very canvas it was originally designed for?

There was magical moment when I watched House of Cards for the first time. All of the sudden Frank Underwood started talking to me. He told me about his plans and even told me some dirty little jokes. It was the first time I had seen anything like it. A little awkward at first but for me, it soon became one of the show’s most iconic elements. I felt as if I was part of the plot.

In movie making this concept is referred to as breaking the fourth wall.

What happens when we apply the same idea to conversational interfaces?

Let’s imagine I’d like to send you push notifications. UX studies repeatedly showed, that asking users for permission works better if they understand the reason, the why.

We can take this idea and adapt it for a conversational context. In my case, the interface could say something like:

- “Hey! I just noticed you’re coming here quite often. Do you wan’t to enable push notifications, so I can notify you immediately when I’ve got something new to share?”

The user either pick “Yes! Sounds good!” or “No. Thanks!”. If the user picks yes… The conversation continues…

- “Awesome! 🙌 There is a pop-up dialog in the upper right corner of the browser. Click on allow and we’re all set!”

User clicks on “allow” and the conversational interface immediately reacts to the users’ action.

- “Awesome! I feel like this is the start of a wonderful friendship 🙏”.

This is just a way to illustrate the concept of breaking the fourth wall in conversational design. A conversation can, and perhaps even should, continue off canvas.

Conclusion

Designing conversational experiences is hard because the concept of a conversation comes with lots of expectations. When those expectations are met, we feel the interface is natural but as soon as they are violated, even in the most subtle way, we feel that something is amiss.

Adding a conversational experience to a website is a way too limiting approach. It’s a fun experiment but it barely exploits the potential of conversational UI’s.

As messaging services like Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, Line and others start creating better integration with 3rd party services, they can add substantally more value to our everyday interactions. Without the need to install yet another app.

Building conversational interfaces doesn’t just come with lots of technological challenges, it also has lots of social ones. As designers, it’s our responsibility to solve this part of the problem.

The future of conversational interfaces aren’t chat bubbles. It’s rich experiences that seamlessly embed and integrate 3rd party services and content into our everyday tools.

So let’s start thinking outside the rectangle, outside the grid and even… outside the bubble.

MEDIUM